Research Overview

Background

The human body consists of approximately 40 trillion cells, and each cell

houses totally about 2 meters of human genome DNA. Negatively charged DNA

is wrapped around positively charged histones to form nucleosomes (Fig.

1, left). Chromatin refers to nucleosomes associated with other proteins

and RNAs. How can such a long nucleosome chain be packed into a tiny cell,

and how does it behave in living cells? Even 70 years after the discovery

of the DNA double helix structure, this remains a fundamental question

in biology.

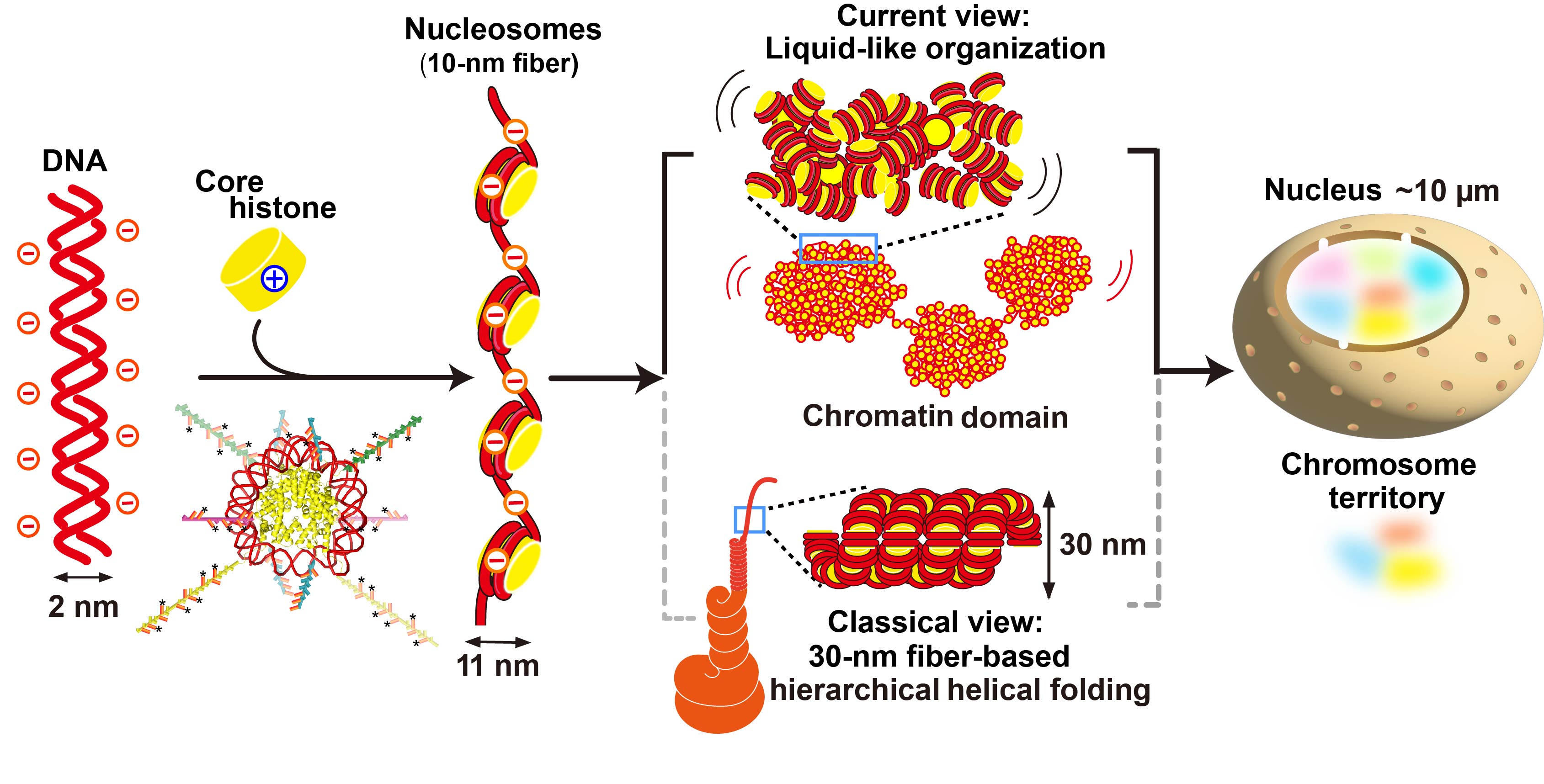

Figure 1.Schematic of DNA, nucleosomes, and chromatin domains. The emerging model of chromatin organization in living cells is shown in the upper panel, whereas the classical model is shown in the lower panel. Reproduced from Maeshima, PJASB 2025.

In the classical textbook model, nucleosomes were thought to fold into

regular 30-nm chromatin fibers and then into progressively thicker fiber

structures through hierarchical helical folding (Fig. 1, lower middle).

If this were the case, proteins would need to repeatedly unwind multiple

layers of higher-order structures to access specific DNA regions. Does

such a process really occur in living cells?

For more than two decades, we have tackled this question. We showed that

strings of nucleosomes in living human cells do not form regular, periodic

hierarchical structures including the 30-nm fiber, but instead fold irregularly

(Fig. 1, upper middle)(Maeshima et al., Curr Opin Cell Biol 2019). Based on this irregular folding, we hypothesized that nucleosomes

are not strongly constrained and that chromatin can be physically dynamic.

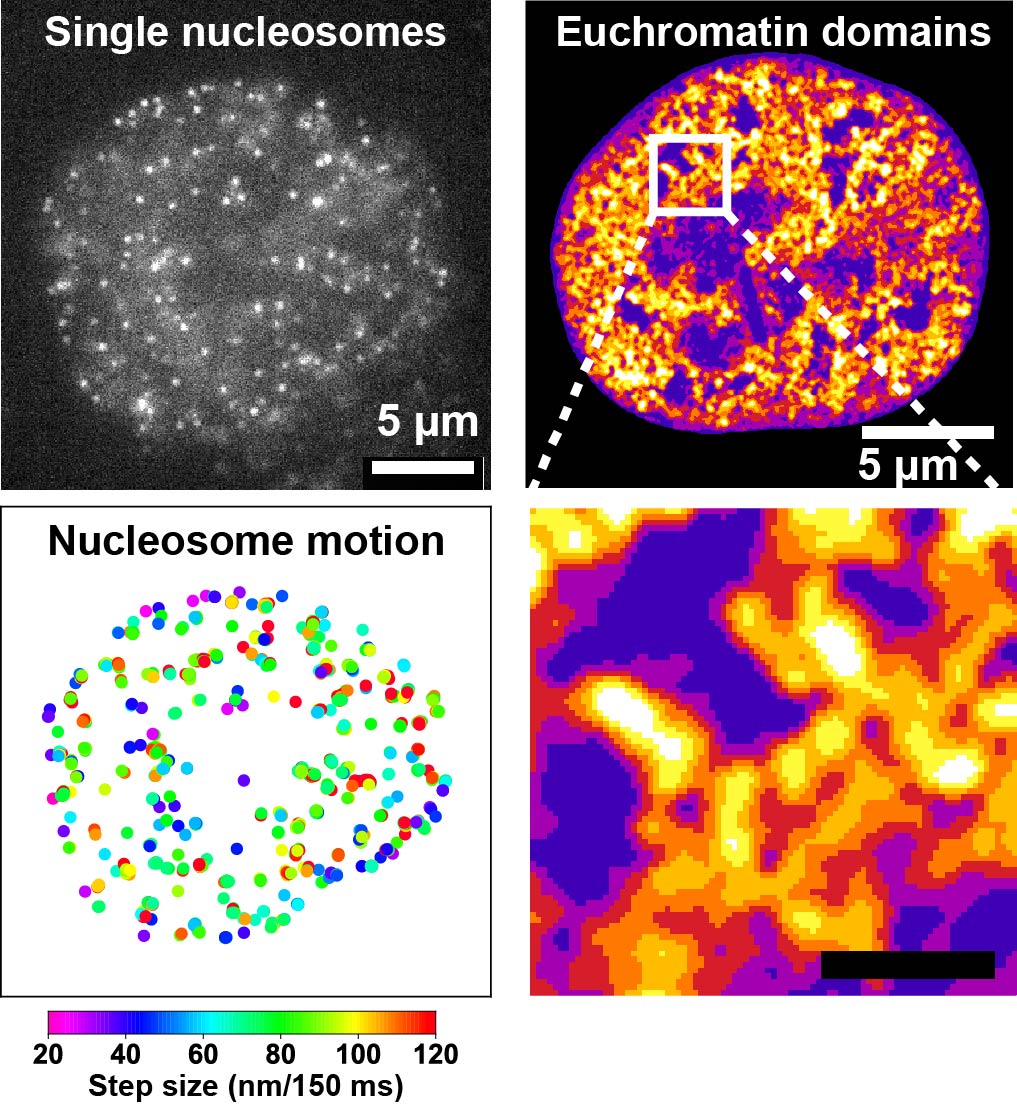

Indeed, by tracking individual nucleosomes in living cells using single-molecule

microscopy, we found that nucleosomes fluctuate dynamically in place and

exhibit liquid-like behavior on short time scales (Fig. 2, left; movie)(Iida

et al., Science Adv 2022; Nozaki et al., Science Adv 2023). Furthermore, super-resolution microscopy revealed that nucleosomes

form ~200-nm condensed chromatin domains (Fig. 2, right)(Nozaki et al.,

Mol Cell 2017; Nozaki et al., Science Adv2023; Iida, Shimazoe et al. bioRxiv2025).

Many genome processes, including DNA replication and transcription, are

thought to proceed with chromatin domains as functional units. We have

also shown that nucleosome fluctuations facilitate protein access to DNA

within chromatin domains (Hihara et al., Cell Rep 2012).

Figure 2.Left: Each dot represents a single nucleosome. By precisely localizing the center of each dot, nucleosome motion can be measured with sub-10-nm precision (Minami et al., Science Adv 2025). Right: Super-resolution chromatin image by structured illumination microscopy (SIM), showing that euchromatin forms condensed domains (Iida, Shimazoe et al., bioRxiv2025).

Single-nucleosome movie(50 ms/frame): Each dot represents a single nucleosome, fluctuating in

place (Iida et al., Science Adv 2022).

Research Topics

We aim to clarify, in living cells, the nature of chromatin domains—especially

their physical properties—and to understand how chromatin domains contribute

to genome functions such as DNA replication, DNA repair, and transcription.

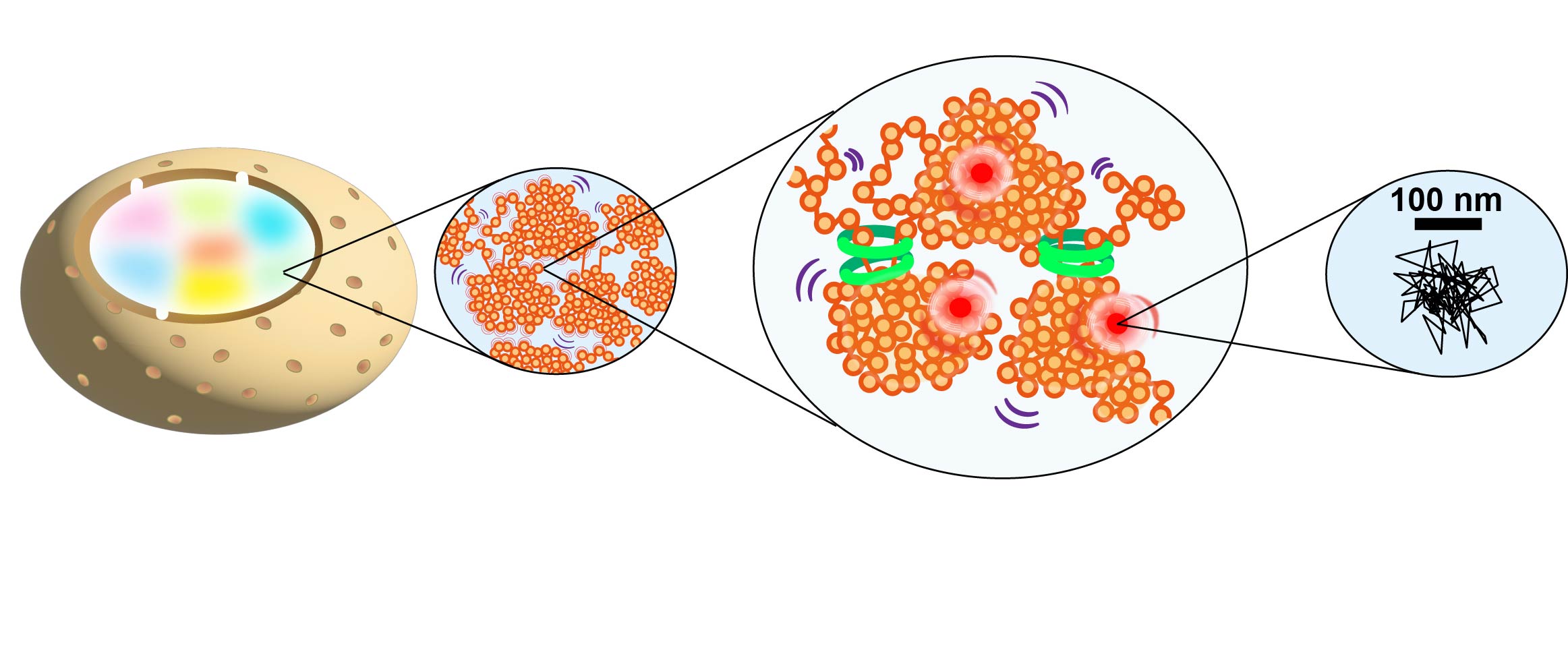

Ongoing projects include: 1. Building a new super-resolution microscopy

systemWe are building a new imaging platform that combines structured illumination

microscopy (SIM), which visualizes chromatin domains in living cells, with

single-molecule microscopy, which tracks the motion of individual molecules

(Fig. 2). Using this system, we observe the structures of chromatin domains

in living human cells and the behavior of nucleosomes and other protein

molecules inside and outside domains (Fig. 3)(Shimazoe et al., bioRxiv 2025).

1. Building a new super-resolution microscopy system

We are building a new imaging platform that combines structured illumination

microscopy (SIM), which visualizes chromatin domains in living cells, with

single-molecule microscopy, which tracks the motion of individual molecules

(Fig. 2). Using this system, we observe the structures of chromatin domains

in living human cells and the behavior of nucleosomes and other protein

molecules inside and outside domains (Fig. 3)(Shimazoe et al., bioRxiv 2025).

Figure 3.We visualize the structures of euchromatin and heterochromatin domains in living cells and track the motion of nucleosomes and other proteins using the new microscopy system. We then analyze trajectories of nucleosomes and proteins (right).

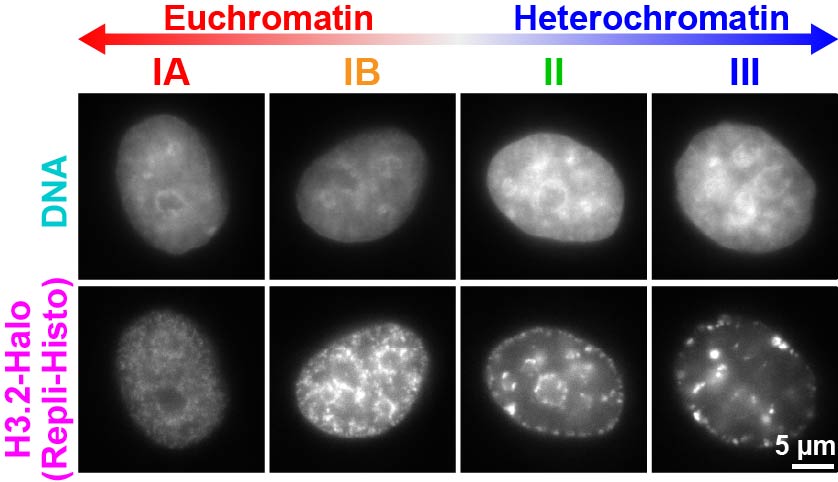

2. Developing specific labeling methods for euchromatin and heterochromatin

Chromatin consists of transcriptionally active euchromatin and transcriptionally

inactive heterochromatin. While biochemical differences such as histone

modifications are well studied, physical differences between euchromatin

and heterochromatin in living cells remain poorly understood. To address

this, we developed replication-dependent histone labeling (Repli-Histo

labeling), a method to fluorescently label euchromatin and heterochromatin

specifically in living cells (Fig. 4)(Minami et al., Science Adv 2025).Using SIM and single-molecule microscopy (Fig. 2), we aim to quantify

the trajectories of nucleosomes and proteins inside and outside euchromatin

and heterochromatin domains (Fig. 3). We analyze the physical properties

of each domain and how proteins access DNA within domains. We further combine

experiments and computational modeling to clarify the nature of chromatin

domains and the mechanisms of domain formation.

Figure 4.Repli-Histo labeling enables specific labeling of euchromatin and heterochromatin. Upper: DNA staining by DAPI. Lower: Repli-Histo labeling. Chromatin can be labeled in four classes—IA and IB (euchromatin) and II and III (heterochromatin)(Minami et al., Science Adv 2025).

We aim to understand genome functions such as transcriptional regulation from the viewpoint of the physical properties of chromatin domains. Using normal cells, various cancer cells, senescent cells, and disease models, we investigate how changes in the physical properties of chromatin domains relate to cellular dysfunction and differentiation.

References:

1. Maeshima K. (2025) The shifting paradigm of chromatin structure: from

the 30-nm chromatin fiber to liquid-like organization. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci101:339–356. doi:10.2183/pjab.101.020.

2. Maeshima K, Ide S, Babokhov M. (2019) Dynamic chromatin organization

without the 30-nm fiber. Curr Opin Cell Biol 58:95–104. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2019.02.003.

3. Iida S, Shinkai S, Itoh Y, Tamura S, Kanemaki MT, Onami S, Maeshima

K. (2022) Single-nucleosome imaging reveals steady-state motion of interphase

chromatin in living human cells. Science Adv8: eabn5626. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abn5626.

4. Nozaki T, Imai R, Tanbo M, Nagashima R, Tamura S, Tani T, Joti Y, Tomita

M, Hibino K, Kanemaki MT, Wendt KS, Okada Y, Nagai T, Maeshima K. (2017)

Dynamic organization of chromatin domains revealed by super-resolution

live-cell imaging. Mol Cell 67: 282–293.e7. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2017.06.018.

5. Nozaki T, Shinkai S, Ide S, Higashi K, Tamura S, Shimazoe MA, Nakagawa

M, Suzuki Y, Okada Y, Sasai M, Onami S, Kurokawa K, Iida S, Maeshima K.

(2023) Condensed but liquid-like domain organization of active chromatin

regions in living human cells. Science Adv9: eadf1488. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adf1488.

6. Iida, S., Shimazoe, M.A., Minami, K., Tamura, S., Ashwin, S.S., Higashi,

K., Nishiyama, T., Kanemaki, M.T., Sasai, M., Schermelleh, L., Toyoda,

A., Kurokawa, K., Maeshima, K. (2025) Cohesin prevents local mixing of

condensed euchromatic domains in living human cells. bioRxiv. doi:10.1101/2025.08.27.672592.

7. Hihara S, Pack CG, Kaizu K, Tani T, Hanafusa T, Nozaki T, Takemoto S,

Yoshimi T, Yokota H, Imamoto N, Sako Y, Kinjo M, Takahashi K, Nagai T,

Maeshima K. (2012) Local nucleosome dynamics facilitate chromatin accessibility

in living mammalian cells. Cell Rep 2:1645–1656. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2012.11.008.

8. Minami K, Nakazato K, Ide S, Kaizu K, Higashi K, Tamura S, Toyoda A,

Takahashi K, Kurokawa K, Maeshima K. (2025) Replication-dependent histone

labeling dissects the physical properties of euchromatin/heterochromatin

in living human cells. Science Adv 11: eadu8400. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adu8400.

9. Shimazoe MA, Huertas J, Phillips C, Ide S, Tamura S, Farr S, Ashwin

SS, Sasai M, Collepardo-Guevara R, Maeshima K. (2025) Linker histone H1

functions as a liquid-like glue to organize chromatin in living human cells.

bioRxiv. doi:10.1101/2025.03.05.641622.

10. Otsuka A, Shimazo MA, Watanabe S, Minami K, Tamura S, Kiyono T, Takeshita

F, Maeshima K. (2026) Cell Structure and Function. doi:10.1247/csf.25147

▲Page top